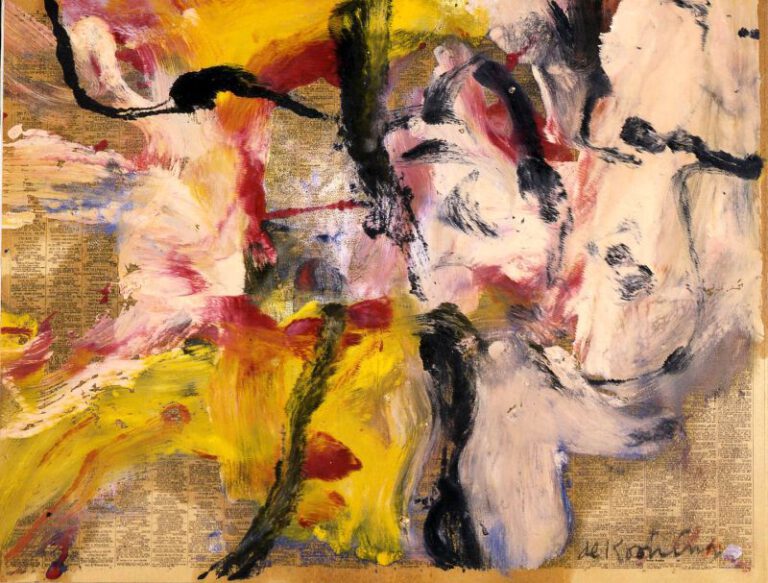

“I paint this way because I can keep putting more and more things in it – drama, anger, pain, love, a figure, a horse, my ideas about space. Through your eyes it again becomes an emotion or an idea.”

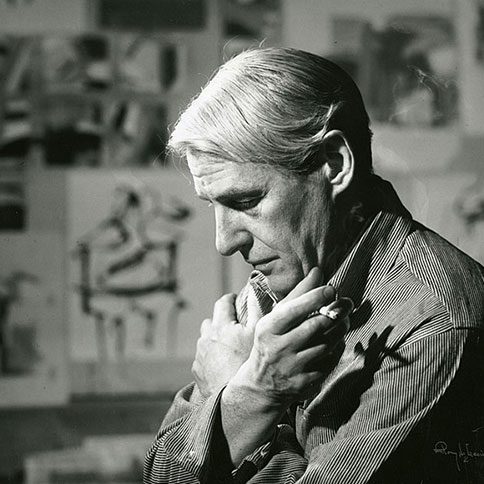

Born in Rotterdam in 1904, the Abstract Expressionist Willem de Kooning moved to the United States at the age of twenty-two. In New York he quickly fell under the sway of the lyrical freedom of jazz and the abstract art created under its influence. He studied the work of Henri Matisse and developed particularly close friendships with contemporaries, including John Graham and Arshile Gorky. De Kooning eventually became a crucial link between European modernism and the New York School. In 1929, during the Great Depression, de Kooning was commissioned to design public murals, working under Fernand Léger. Though his studies for the murals were never realized, they were among de Kooning’s first abstractions, and the experience spurred him to pursue art-making as a full-time occupation.

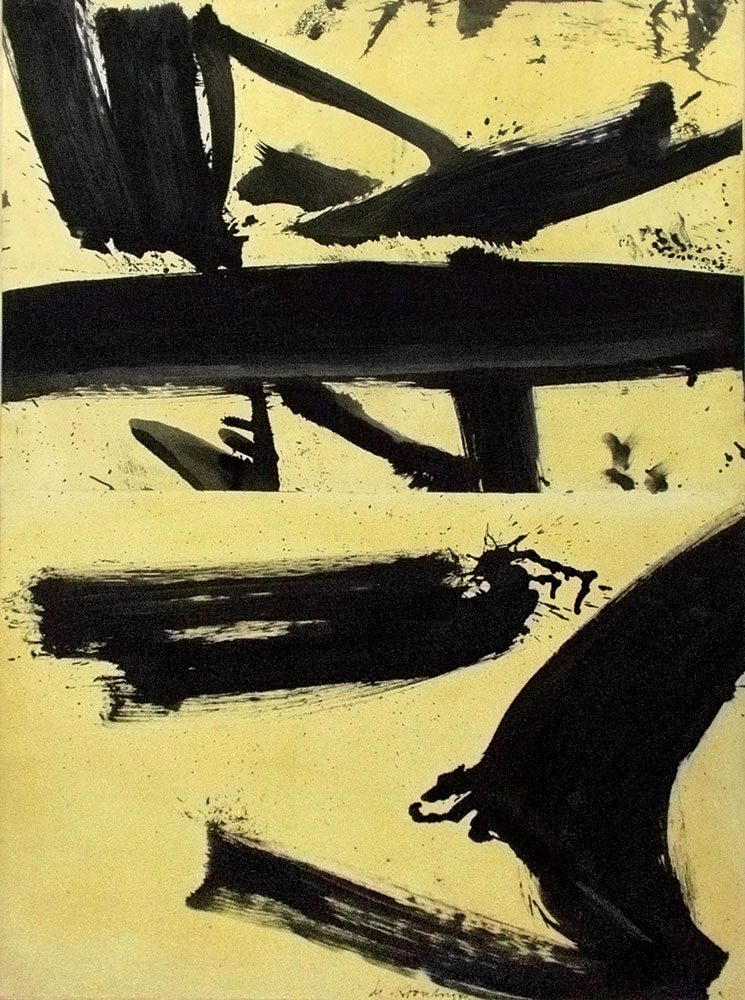

During the course of a career lasting nearly seven decades, de Kooning developed a wide array of styles, ranging from abstraction to figuration, which often merged and fed into each other. The female figure was an especially potent – and controversial – subject. Large brushes and fluid paints were the tools of de Kooning’s earlier trade as a house painter, and he continued to utilize these throughout his artistic career, combining physical labor with endless experimentation: “I never was interested in how to make a good painting . . . ,” he once said. “I didn’t work on it with the idea of perfection, but to see how far one could go . . . .” De Kooning used oil and enamel sign paint to make his black-and-white abstractions, which he began creating in 1948, the year of his first solo exhibition. Black and White consists of two sheets of yellowish-white paper covered with black forms. Tensile, energetic, diaphanous streaks and drips of paint pack densely into a composition of great economy, interlocking with each other. Created with great bravado and enormous certainty, they resemble illegible letters or vaguely human forms, supporting the artist’s claim that “even abstract shapes must have a likeness.”

Adina Kamien