Scroll right to see the works

The artist Ad Reinhardt claimed in 1962 that “The one object of fifty years of abstract art is to present art-as-art and as nothing else…making it…more absolute and more exclusive – non-objective, non-representational, non-figurative, non-imagist, non-expressionist, non-subjective.”

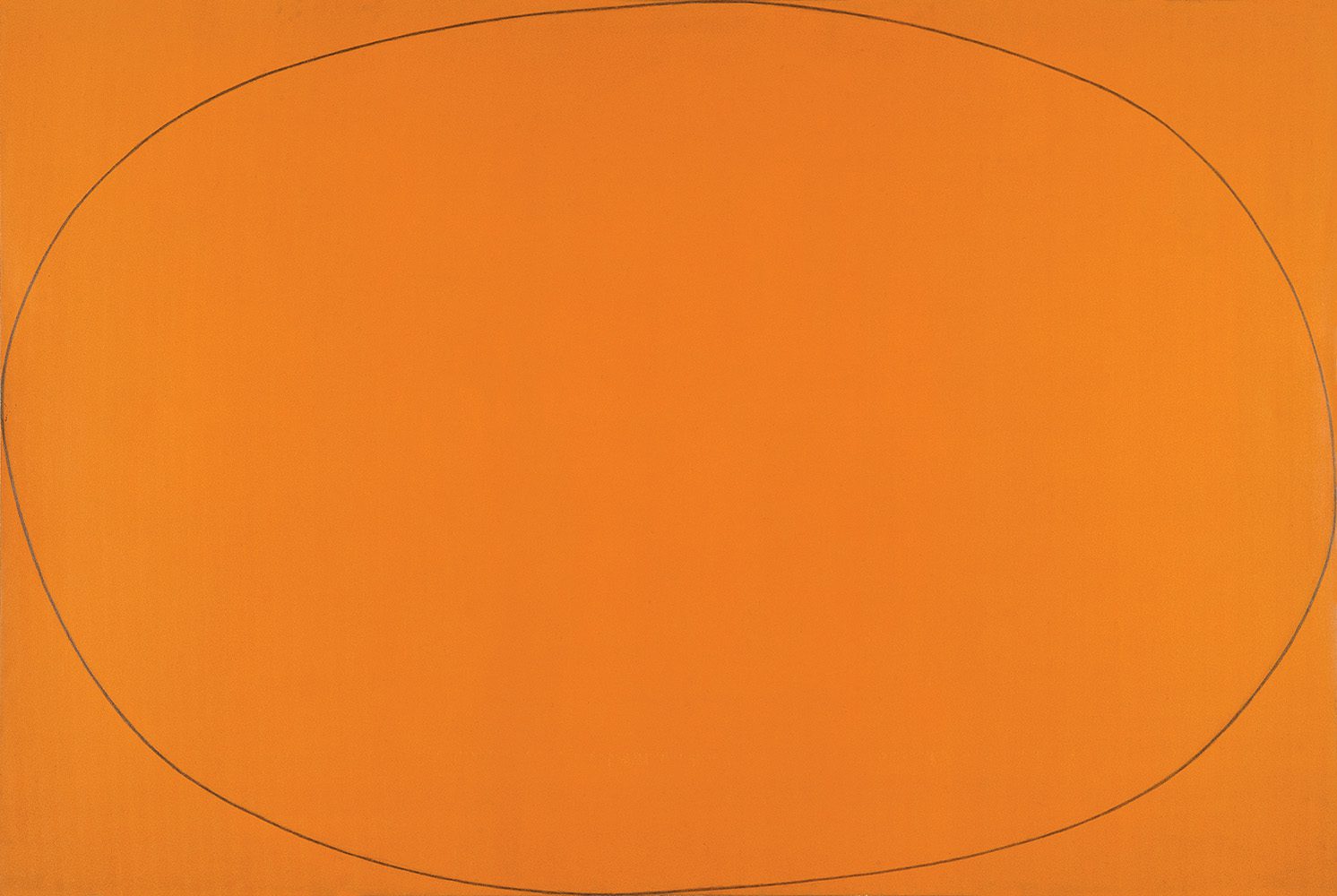

This part of the exhibition explores the notion of “pure abstraction,” examining Hard-Edge, Minimalist, and Postminimalist artworks that seek fundamental elements, essential structures, or inherent geometries. Extending the idea that art should exist within its own realm and not represent either outer reality or inner emotion, artists such as Ad Reinhardt, Agnes Martin, and Robert Mangold wanted viewers to respond only to what was in front of them: medium, material, and form. As Frank Stella succinctly said about his own paintings, “What you see is what you see.”

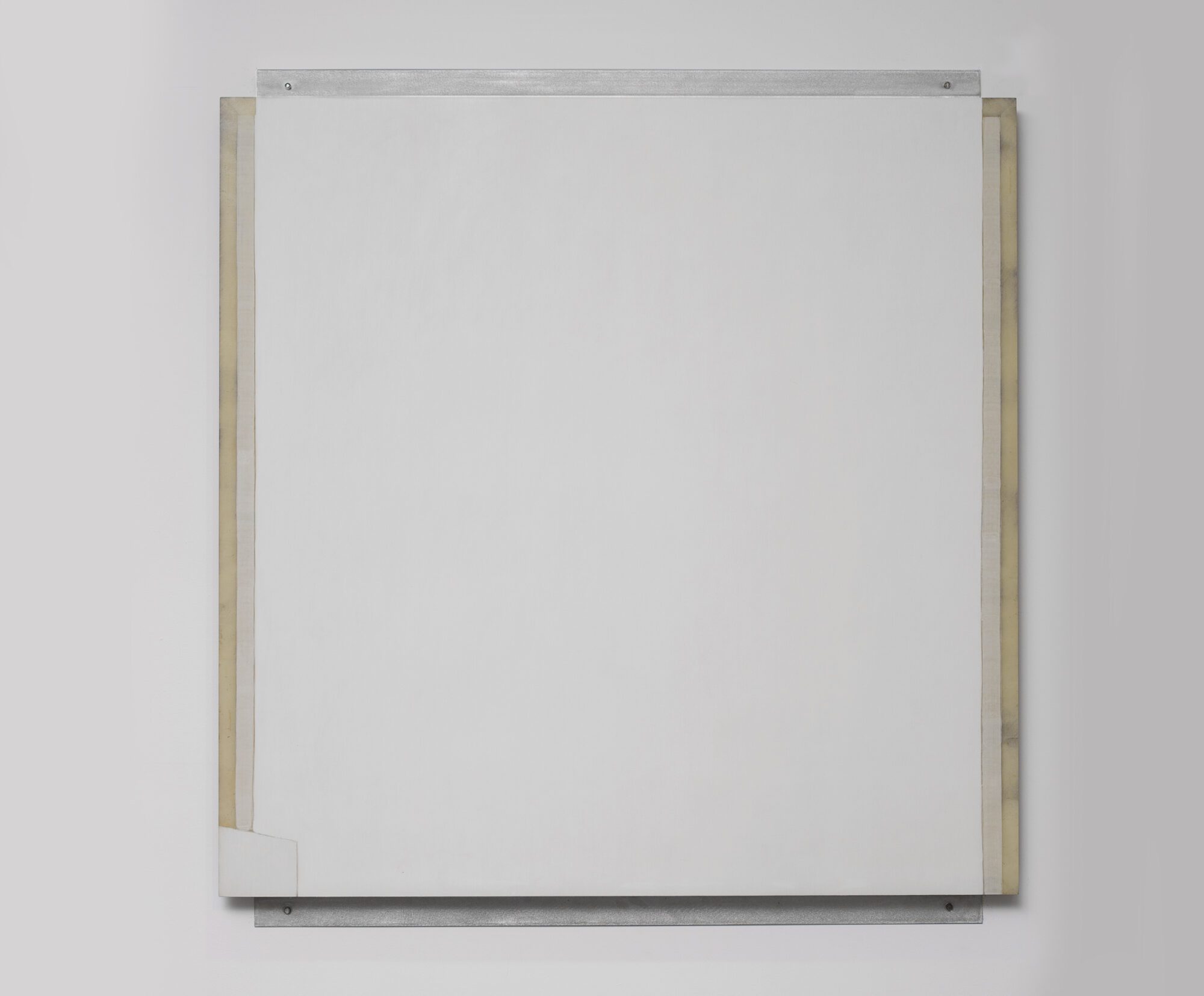

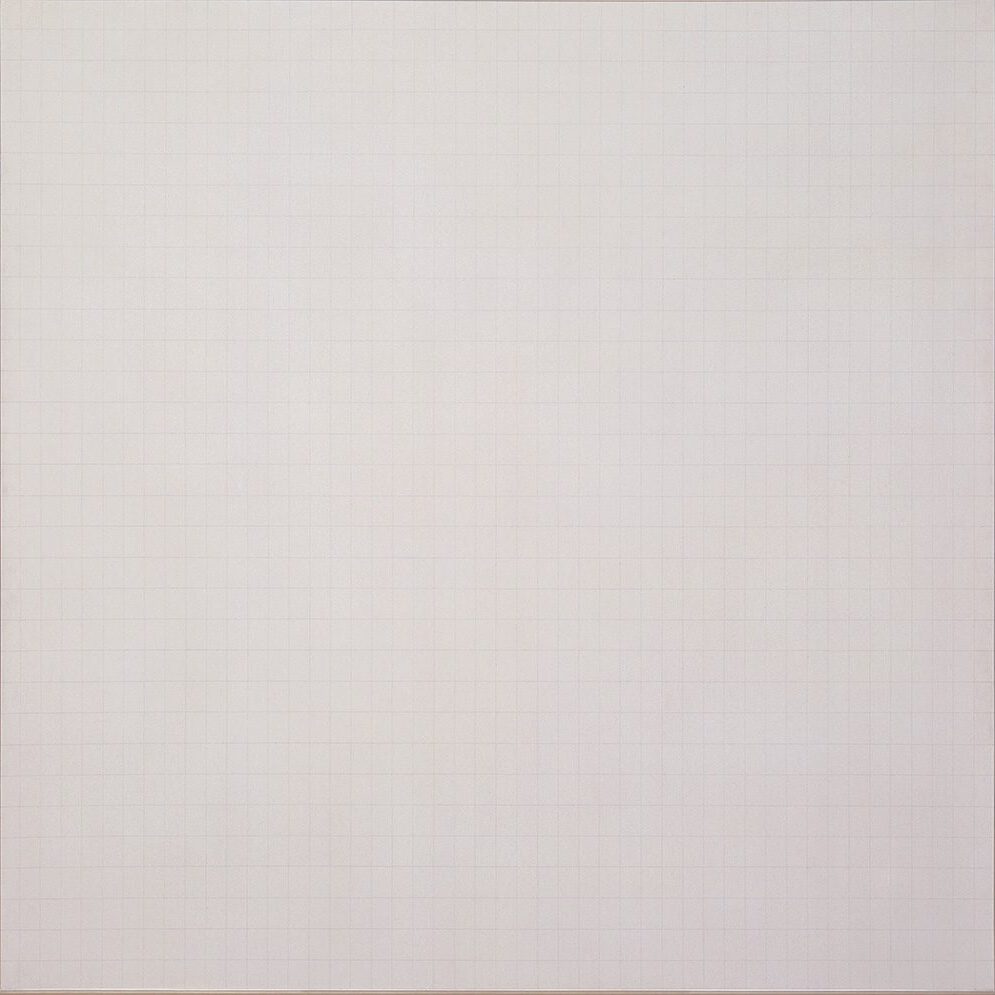

Minimalism emerged in the late 1950s when artists began to turn away from the gestural art of the previous generation towards geometric abstraction. It flourished in the 1960s and 1970s, with artists seeking a highly purified form of art and striving for qualities such as truth, order, simplicity, and harmony. Robert Ryman, identified with the movements of monochrome painting, minimalism, and conceptual art, and is best known for abstract white-on-white paintings. Also exploring the monochrome, Agnes Martin’s practice was tethered to spirituality and drew from a mix of Zen Buddhist and American Transcendentalist ideas. For Martin, painting was “a world without objects, without interruption… or obstacle. It is to accept the necessity of … going into a field of vision as you would cross an empty beach to look at the ocean.” Like Martin, Michael Gross’s works are geometric and minimalist, but linked to natural form and laden with feeling. He simplifies images of people and the Israeli landscape in order to concentrate on proportion, broad areas of color, and the size and placement of each element. His paintings are architectural, juxtaposing large, off-white panels with patches of tone, adding textured materials such as wooden beams, burlap, and rope.

Geometry and non-perspectival space became a metaphor for the modern world. According to contemporary geometric painter Peter Halley, “[if in the past] geometry provided a sign of stability, order, and proportion, today it offers an array of shifting signifiers and images of confinement and deterrence.”