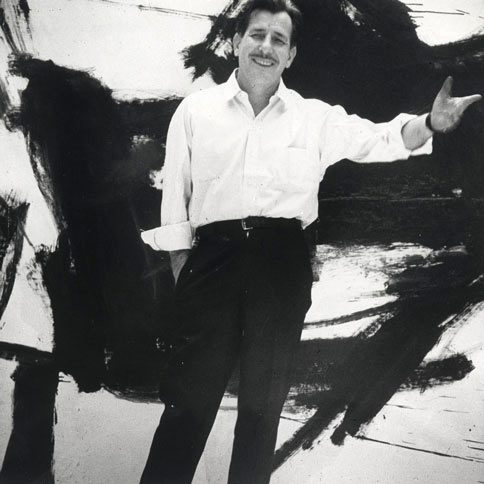

Black, rough brushstrokes on a white painted surface are the signature style of Franz Kline. Like many of the New York School artists, such as Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, and Willem de Kooning, Kline’s works embody the idea of “action painting.” In the aftermath of World War II, Kline and his fellow painters looked for new modes of artistic expression, distinct from American Realism and European Cubism. Action Painting emphasized the spontaneous, “unconscious” side of creation.

In 1948 or 1949 Kline visited de Kooning in his studio, and the latter showed him the possibility of enlarging his drawings by projecting them onto canvas, revealing how well they worked as wall-sized compositions. Kline soon abandoned figuration in favor of abstraction, and easel painting for mural-scale works. His monochromatic palette, together with brushstrokes that resemble an exaggerated version of Japanese ink calligraphy, caught the attention of the Bokujin-kai, a Japanese avant-garde association of calligraphers. Kline and the group’s leader, Morita Shiryū, exchanged letters regarding the relationship between abstraction and calligraphy. While some scholars claim that Kline was directly influenced by traditional Japanese art, the artist later rejected this claim, siding with American art critics who, influenced by growing cultural chauvinism, slandered traditional and modern Japanese influences and insisted that Abstract Expressionism was a distinctly American invention. Kline stressed that unlike calligraphy paintings, in his work black carries the same importance as white.

Although carefully planned, the composition of Bethlehem exudes a feeling of spontaneity and physical momentum. Within the gestural chaos of the painting, the artist creates a balance between intense black brushstrokes and a white surface, allowing for space and breath. The abstract image conveys a great sense of movement, sensuousness, and dynamism.

Yam Traiber