German artist and filmmaker Hans Richter was devoted to breaking with the conventions of art history and finding new insights into the creative process. “The life we led, our follies and our deeds of heroism, our provocations . . . were all part of a tireless quest for an anti-art, a new way of thinking, feeling and knowing,” he said.

Born in Berlin to a wealthy Jewish family, Richter was injured in battle during World War I. While recovering at a medical facility in Zurich, he became acquainted with the Dadaists Hugo Ball, Tristan Tzara, and Jean (Hans) Arp. During this period, he also befriended the Swedish filmmaker Viking Eggeling, with whom he would collaborate on a number of pioneering abstract films. Forced to flee the persecution of the Nazi regime in the 1930s, Richter escaped to the Soviet Union and then to the United States. He spent his later years in Connecticut, where he returned to painting and published the book Dada: Art and Anti-Art in 1965.

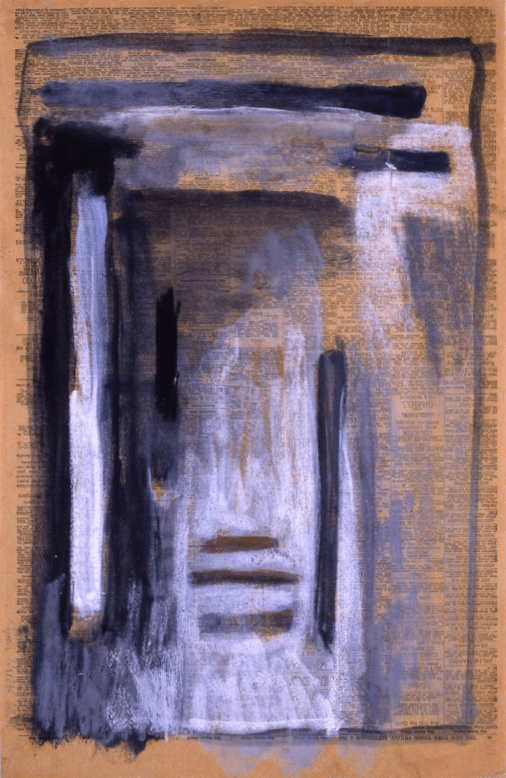

Scroll, Black and White, Abstract is shaped like a Japanese hanging scroll. With its black vertical brushstrokes of varying degrees of viscosity, it recalls Richter’s 1919 scroll drawing Preludium. He described its evolution and relationship to film: “In 1919, I realized the promise of movement in the scroll drawings. . . . [P]ainting had led me to problems of dynamism, dynamism led me to kinetic problems, and kinetic problems could ultimately be realized only in film. Although I started making films in 1921, I still was mostly interested in them as solutions to the problems that I had met in painting. It took me a while to get into the films themselves.” Richter and Eggeling worked together for the next three years, producing multiple drawings which they rearranged repetitively, trying to find relationships and create rhythms. The “scrolls” were a new artistic syntax in which the eye traveled a prescribed route from beginning to end, ultimately leading them to film, extending this dynamic potential into actual kinetic movement.

Richter considered the scroll as “a new (dating from 4000 B.C.!) art which . . . ought to become a modern medium of expression. It must, in fact, as there are sensations to be derived from it which can be experienced in no other way, either in easel painting or in film.” For him, “The scroll belongs to the realm of time, but in a special way. It is not physiological movement but rather a psychological one. It is between painting and film. As such it is a movement of the mind, movement which is kept in balance but which still might break out . . . any moment into kinetic action. One may consider it the ultimate harmony of non-movement, as part of movement” (quoted from Hans Richter by Hans Richter, ed. Cleve Gray, New York, 1971).

Adina Kamien