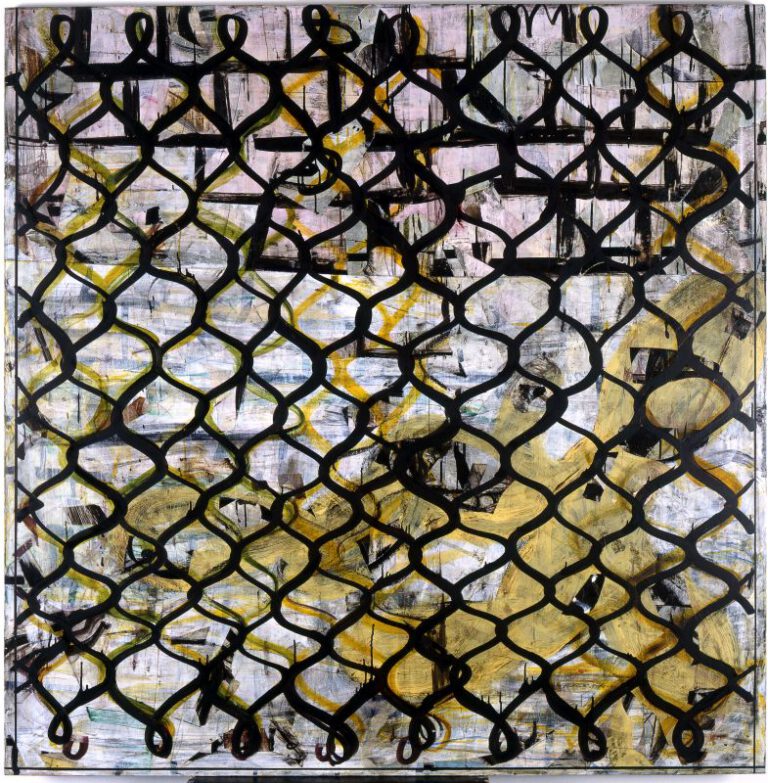

At first glance, Terrazzo 14 looks like an abstract work of art, recalling the chance formations of Pollock’s action paintings, yet a closer look reveals that its subject is actually a real material object – a familiar product replete with local, social, and political meanings.

The triptych depicts terrazzo tiles (of the kind known as “sesame”) made of molded and polished concrete, gravel, and sometimes also marble fragments. Glossy tiles such as this were popular in Israel from the 1920s to the 1990s. Until the first Intifada, they were mainly manufactured by Palestinians. Using a decollage technique, Geva applies a layer of paint on the canvas; next he sticks pieces of paper or cloth onto it, applies another layer of paint on the entire canvas, and then removes the glued pieces, exposing the layer of paint underneath.

Geva’s works deal with the tension between minimalism and formalism on the one hand and symbolic, archetypal, and politically charged images on the other; between random, abstract forms and forms that are laden with political overtones taken from the local architecture, traditional clothing (keffiyeh), and even games (backgammon). Geva follows in the footsteps of American abstract painting, creating an aesthetic and spiritual experience through shapes, blots, and lines, while at the same time using ready-made visual tropes (iron bars, keffiyehs, tiles) – thus synthesizing Abstract Expressionism with a specific place, local symbols, and Islamic ornamentation. In Geva’s art, abstraction is not detached from a particular place or from its existential political questions, nor does it serve a purely aesthetic purpose. In contrast with the typically suspicious attitude of the Israeli public, Geva appropriates forms taken from the local Muslim culture and gives them pride of place in his work.

Ido Targano