In keeping with the tenets of Minimalism, Robert Mangold’s paintings reflect an “abiding desire to make the work be a unity. . . . I wanted the periphery line and the internal line, the surface, color, etc. to be equal. . . . No one area of the painting should be more important than another – even the idea” (quoted in Robin White, “Interview with Robert Mangold,” View 1 [1978–79]: 7). Mangold posits the artwork as a self-contained entity. Shorn of all illusion, the work reveals itself directly to the viewer, who is located in the same real space and real time as the art object.

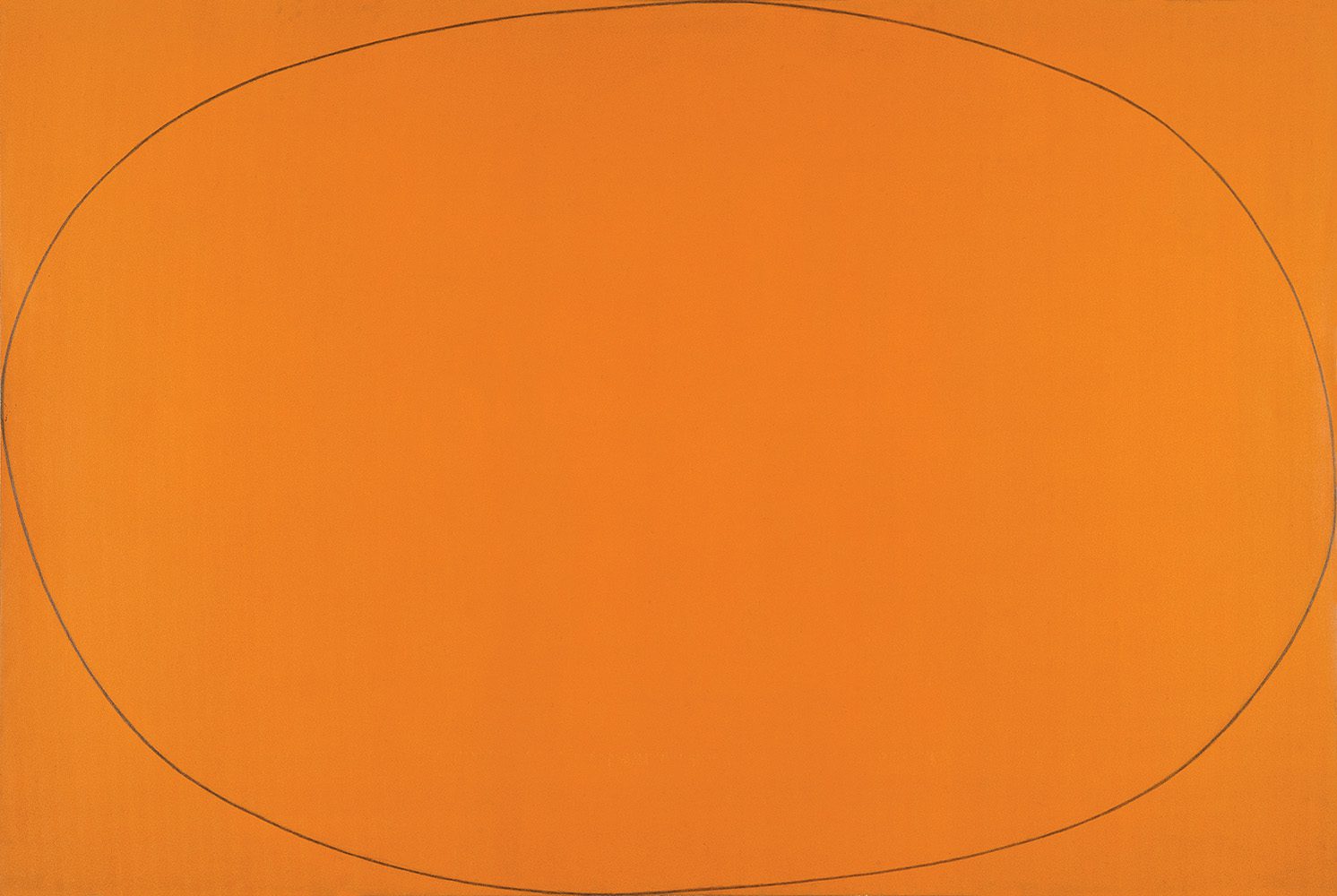

To Mangold, geometry is a tool – a language – but not a theme. Employing geometric elements, he creates neutral, anonymous, self-referential forms. The oval in Distorted Ellipse within a Rectangle may seem, at first glance, a perfect example of its type. On closer scrutiny, however, it becomes obvious that it is asymmetrical and warped – “distorted,” as the work’s title indicates. Mangold drew the oval by hand, thus forsaking pure geometry. It becomes difficult to determine whether the paradigm or the painter is at fault for the deviation from the ideal form and whether the defect is, in fact, perceptual, conceptual, or technical.

Lynn Cooke